Editorial Work

Series Editor for the University of Calgary Press: Small Cities: Sustainability Studies in Community and Cultural Engagement

This new series is interested in discovering and documenting how smaller communities in Canada and elsewhere differ from their larger metropolitan counterparts in terms of their strategies (formal and informal) for developing, maintaining, and enhancing community and cultural vitality, particularly in terms of civic engagement, artistic animation, and creative place-making and place promotion; cultural mapping; new immigrant incentives; community-university partnerships; partnerships with Indigenous communities; local sustainability planning, issues of homelessness and housing; food security; women, children, and social justice; and social activism.

This new series is interested in discovering and documenting how smaller communities in Canada and elsewhere differ from their larger metropolitan counterparts in terms of their strategies (formal and informal) for developing, maintaining, and enhancing community and cultural vitality, particularly in terms of civic engagement, artistic animation, and creative place-making and place promotion; cultural mapping; new immigrant incentives; community-university partnerships; partnerships with Indigenous communities; local sustainability planning, issues of homelessness and housing; food security; women, children, and social justice; and social activism.

Series Editors:

Will Garrett-Petts, Professor of English and Vice-President of Research (Interim) at Thompson Rivers University

Nancy Duxbury Carreiro, Senior Researcher, Centre for Social Studies, University of Coimbra, Portugal, and Co-coordinator of its Cities, Cultures, and Architecture Research Group

Some Current Research Projects

“Supported by a SSHRC Insight Grant (2020-2024), and working with Co-Researcher Sharon Karsten, our research team is exploring the Cultural Mapping of Lived/Living Experiences of the Drug Poisoning Crisis in BC’s Small Cities.

“Supported by a SSHRC Insight Grant (2020-2024), and working with Co-Researcher Sharon Karsten, our research team is exploring the Cultural Mapping of Lived/Living Experiences of the Drug Poisoning Crisis in BC’s Small Cities.

As a research methodology, cultural mapping seeks to combine the tools of modern cartography with vernacular and participatory methods of storytelling to represent spatially, visually, and textually the authentic knowledge and memories of local communities. Such mapping has become increasingly employed by governments, most notably municipalities, and academics worldwide, often under the premise that it holds an ability to engage and connect with populations and communities not normally inclined towards political/academic participation. Within the context of the Canadian drug overdose crisis, cultural mapping has increasingly been pursued as a methodology for understanding the ‘lived reality’ of the crisis. Through such formats as photo-voice and graphic illustration, people at the heart of the crisis, notably those who use drugs, are invited to share their experiences. Yet while cultural mapping methodologies often pay tribute to the voices of marginalized and vulnerable people, it is our contention that many fail to adequately and authentically represent these voices. This failure often-times takes the form of over-interpretation, whereby the voices of participants become subsumed, as in many graphic facilitation forms of cultural mapping, by the over-arching voice or interpretation of an ‘expert’ — leading to an (often unconscious) over-writing of the voices most affected. Employing a grounded theory approach, and informed by scholarship on vernacular rhetoric, cartography, and communications theory, Garrett-Petts and Karsten are developing and testing optimal ways to code, interpret, and account for the knowledge, memories, and voices represented in cultural maps. In the process, they are generating new knowledge regarding the limits and potentials of involving non-expert community voices in co-created processes of meaning-making, problem solving, and interpretation.

A new publication on this area will be published in 2024: Duxbury, N. and Garrett-Petts, W. F. Re-situating participatory cultural mapping as community-centred work. In Tania Rossetto and Laura Lo Presti (eds.), The Routledge Handbook of Cartographic Humanities. London: Routledge.

“Supported by a Vancouver Foundation Participatory Action Research (Investigate Grant), 2020-2024, an d working in collaboration with Researchers Sharon Karsten, Charmaine Enns, Sara Gifford, Bob Hughes, Sukh Heer Matonovich, Vicki Manuel, Lindsay McGinn, John Powell, Colleen Salter, Catriona De La Torre (Vancouver Island University, Thompson Rivers University, The Comox Valley Art Gallery, The United Way, First Nations Health Authority, the Kwakiutl District Council, the Comox Valley Community Health Network, the City of Kamloops, TRU’s Research Office, ASK Wellness, our research team is engaging in “Cultural Mapping the Drug Poisoning Crisis in Kamloops and Comox Valley, B.C.”

d working in collaboration with Researchers Sharon Karsten, Charmaine Enns, Sara Gifford, Bob Hughes, Sukh Heer Matonovich, Vicki Manuel, Lindsay McGinn, John Powell, Colleen Salter, Catriona De La Torre (Vancouver Island University, Thompson Rivers University, The Comox Valley Art Gallery, The United Way, First Nations Health Authority, the Kwakiutl District Council, the Comox Valley Community Health Network, the City of Kamloops, TRU’s Research Office, ASK Wellness, our research team is engaging in “Cultural Mapping the Drug Poisoning Crisis in Kamloops and Comox Valley, B.C.”

The project involves a community action partnership between university researchers, social service agencies, government representatives and Knowledge Holders. It asks, How can arts-informed cultural mapping as a participatory action research method applied to the drug poisoning crisis help save lives, reduce harm, improve social and community cohesion, and create systems change. The project harbors direct connections with, and commitments from, policy-making organizations, including the City of Kamloops and the Vancouver Island Health Authority. Arts-based and arts-informed epistemological frameworks have, in recent years, been readily embraced by health researchers, especially those looking at the social determinants of health by using techniques such as photovoice. Yet in spite of these developments, artist-led and humanities oriented research approaches addressing wicked multi-faceted socio/cultural/economic/biological problems like the opioid crisis remain rare. Some excellent work on “journey mapping” of the opioid crisis has produced powerful initial results and provides a kind of proof of concept for our current work (BC Patient Safety & Quality Control Council, 2017). But where such approaches also solicit community input, they do not focus consistently on individual voices and experiences. Instead of multiple artist-led processes drawing out stories and maps from locals, health-oriented journey mapping to date tends to consolidate viewpoints by employing a single graphic facilitator, reflecting the work of skilled note-takers and artists visually representing the broad strokes of oral exchanges, typically in workshop and seminar settings. What tends to get lost are the individual voices, the individual records and layers–the mappings–of lived experience. The act of bringing Knowledge Holders and their art-based representations of experience into a community-wide dialogue enables, we argue, a powerful evolution of community potential to develop meaningful solutions to the crisis.

“The Vernacular Rhetoric of Cultural Mapping: Everyday Cartography in the Public Sphere” (Supported by a SSHRC Connections Grant, 2016): Garrett-Petts, W.F. “The Vernacular Rhetoric of Cultural Mapping: Everyday Cartography in the Public Sphere.” Keynote Address presented at ‘Where is Here?’: A Conference on Small Cities, Deep Mapping and Sustainable Futures. Comox Valley Art Gallery and Vancouver Island University http://www.whereishereculturalmapping.com/publications/ Online.

“The Vernacular Rhetoric of Cultural Mapping: Everyday Cartography in the Public Sphere” (Supported by a SSHRC Connections Grant, 2016): Garrett-Petts, W.F. “The Vernacular Rhetoric of Cultural Mapping: Everyday Cartography in the Public Sphere.” Keynote Address presented at ‘Where is Here?’: A Conference on Small Cities, Deep Mapping and Sustainable Futures. Comox Valley Art Gallery and Vancouver Island University http://www.whereishereculturalmapping.com/publications/ Online.

The prospects for, and challenges of, including vernacular voices in the public sphere are perhaps nowhere more keenly felt than in the practice of cultural mapping for community empowerment as defined by UNESCO and its partner organizations. As Nigel Crawhall writes in a 2007 Concept Paper, “Cultural mapping involves the representation of landscapes in two or three dimensions from the perspectives of indigenous and local peoples” –and aims to “create platforms for intercultural dialogue, and increase awareness of cultural diversity as a resource for peace building, good governance, fighting poverty, adaptation to climate change and maintaining sustainable management and use of natural resources” (1). The project of cultural mapping is, as described and at root, utopian in its aspirations, seeking to document, honor and empower the voices of local participants, all the while including them in a larger social justice and community building agenda. Moreover, cultural mapping practices promise access to insider knowledge, to make tangible and visible that which is otherwise intangible and invisible: “Over the last four decades, there has been increasing awareness that some of the most important aspects of human culture are contained in the intangible aspects of cultural practices and knowledge systems. Cultural mapping is one way to transform the intangible and invisible into a medium that can be applied to heritage management, education and intercultural dialogue” (Crawhill 6).

“Defeating Authorship: Revisiting the Museum of Jurassic Technology” (Supported initially by a SSHRC Standard Research Grant, and later by a TRU Research Stipend)

“Defeating Authorship: Revisiting the Museum of Jurassic Technology” (Supported initially by a SSHRC Standard Research Grant, and later by a TRU Research Stipend)

(in collaboration with Emily Hope, The Kamloops Art Gallery)

The Museum of Jurassic Technology is typically described as “[p]art installation art-performance, part curiosity cabinet, part testimony to the fact that truth is stranger than fiction, and purely David Wilson’s creation.” Over and over, the Museum is discussed in terms of “Wilson’s singular vision” (Mathew Roth)—and perhaps most tellingly, the museum has been represented by Weschler and others as a one-man show.

However, in this research, based on a series of interviews conducted over several years with the Museum Director and the museum staff, we want to reconsider The Museum of Jurassic Technology not in terms of the heroic artist, a postmodern gesture or unstable rhetorical trope or a fake modernist museum, but as a research and public art collective—a community at once informed by the tradition of artist house museums (for David does indeed live in a 1951 Spartan Aircraft Spartanette Travel Trailer Coach parked on the museum property) and inflected by a commitment to research and artistic inquiry akin to that pioneered by new genre public art and now a subject under intense reflection in universities and communities.

What the Museum embodies is an alternative narrative space informed by acts of shared community identification with lives, images and artifacts that are truly performative in that they reveal in the lost or forgotten or otherwise silenced vernacular a “capacity for consequence” (Propen). The MJT, we contend, is socially maintained and produced as a kind of dialectic between two highly complementary spaces. One, the public face—the galleries, the bookstore, the tea room, the theatre; the other, a generally private and hidden, seemingly peripheral art and curatorial collective.

“The Rhetoric of the Project: Art at Work and Workers as Artists” (Keynote Presentation for The Spectres of Evaluation Conference, Centre for Cultural Partnerships, University of Melbourne.)

Together with Dr. Lisa Cooke (an Anthropologist), the United Way, the Steelworkers, and ASK Wellness (the Aids Society of Kamloops), I have been documenting a public showers initiative from its inception to the opening—and now its impact (which includes both a video documentary we’ve produced and a related art exhibition on “The Art of Giving and Receiving”). As part of this research, I’ve been worrying the notion of “The Rhetoric of the Project,” exploring how projects and project management are variously defined by the trades volunteers (Steelworkers Local 7619), the union management, and artists (especially community-based artists).

A new publication on this area is under review and is expected to be forthcoming in 2024: Garrett-Petts, W.F., and Evelyn Asiedu. “Art at Work, and Workers as Artists: Project Thinking, Craft, and Creativity in Community-Engaged Research.” Eds. Stuart Poyntz, Kari Grain, and Am Johal. Critical Futures: Community-Engaged Research in a Time of Crisis and Social Transformation. U of Toronto P.

This interest in the “art or craft of giving” has been influenced by my ongoing research on artists working in the community—on their practices, assumptions, and theories. While creating the video documentary on the public showers project, I began to notice a number of striking correspondences between the giving practices of the steelworkers and the public art practices of the artists. Richard Sennett, in his book The Craftsman, makes the case for what he calls “engaged material consciousness,” maintaining that “people invest thought in things they can change, and such thinking revolves around three key issues”: metamorphosis (changing an object, a situation, a procedure or technique), presence (leaving the maker’s mark), and anthropomorphosis (imputing human qualities to raw material). I would argue that these three issues can be usefully correlated with the motives, social norms, and conditions for giving that inform the shower project; and that understanding the charitable and creative work of the Steelworkers invites an appreciation of engaged material consciousness.

I’m especially interested in exploring the rhetoric of the project and how the sense of an ending informs that rhetoric. For the craftspeople volunteering on the shower project, the official opening brought closure. Those interviewed that day spoke enthusiastically and consistently of their desire to move on to the next project. Questions of measurement, of assessing the impact of the project, were referenced as the kind of concerns associated with management—as something removed from the more organic, intuitive, and improvisational acts of making that were seen to constitute the true work accomplished. In this sense, the shower project echoes the practices of those community-engaged artists who speak of their art projects as opportunities for intense but often short-term involvement (and here I’m thinking of those for whom local issues and interactions become the occasion or material for art-making, soon to become the objects of art, important that is at the moments of creation and artistic production—important to “the project”—but something left behind once the artwork has been “completed”). Like the Steelworkers, project completion brings a shared sense of an ending and a felt sense that the work should speak for itself.

This ongoing research engages the proposition that “Thinking and feeling are contained within the process of making” (Richard Sennett, The Craftsman, p. 7)—and in so doing extend Sennett’s three key characteristics of material consciousness to an understanding of project rhetoric and practice. I’m in the process of working out the distinguishing features of an emerging Rhetoric of the Project: “the origin story,” the motive as narrative; the sense of “craft,” “art,” and importance of “materials and working with your hands”; an attachment to expressions of “interest” as a part of the vocabulary of practice, with the project or working hypothesis tending to remain an interest rather than an argument or proposition or statement or plan; “the significance of exploration and improvisational organizational structure,” “material thinking,” and the value of “intuitive communication”—what the Greeks called Kairos, the ability to make the right decision “in the moment”; “the pride in the work”; “the relative unease with measurement and statements”; the “signature” of the artists/workers; and the focus on “the project” and the “sense of an ending.”

“Unstated Provocations: Understanding the Artist Statement as Exhibition and Performance” (Initial research supported by a SSHRC Standard Research Grant)

For the last 10 years or so, my colleagues, students, and I have been exploring the rhetoric of artist statements—that is, the power of what artists say and write about their own work. A work may make a statement, may speak for itself as it were; but the artist’s own words can also affect audience response to that work. Statements, we’ve come to appreciate, present themselves as part of an array of “artist writing and talk”—as artists’ interviews, journals, albums, sketchbooks, and all manner of private correspondence and theorizing that, when made public, form meta-narratives speaking to and about the work. Although such self-reflective discourse seems ubiquitous, not all artists and curators are comfortable with the public foregrounding of private aesthetics, written typically, as Derrida reminds us, “in view of their own self-effacement.” Artist statements call attention not only to the artworks they introduce but also to themselves—and, we would argue, to “the artist” as creative and critical agent. Artist statements are palimpsests, presenting, in words, a narrative or argument apparent beneath or beside or overlaying or in some kind of proximity to each principal visual representation.

In an effort to better understand the role of statements in creative practice, we have drawn upon the insights of British artist-researcher, Chris Rust, who has published a remarkably useful article on the “unstated contributions” of artists. He maintains—and we think this a key point—that artist-researchers struggle to gain conventional recognition for their research contributions because their work does not fulfill the obligation of “contributing new knowledge.” Where non-artists state explicitly their contributions, their findings, according to Rust artists make unstated contributions, provocations or invitations to an audience (69-70). Artists engage in non-propositional inquiry, in creation “at the point of utterance” (as James Britton once said of writing). The point of leaving their contributions unstated is arguably central to artists’ research methods and practices; it is also we argue a point of profound tension when composing artist statements.

On the one hand, when presented as public documents, what artists say or write about their own works is inherently interesting. Their words, their statements, may provide us with unique insights into their practices. As Gabriele Detterer puts it, “The statement [is] an articulation of the artist’s aesthetic position, free of intervention by an art critic bent on interpretation” (9). On the other hand, for the artist herself, there’s always the risk of saying too much, of over-explaining and thus leaving the viewer little room for individual discovery. Words can get in the way of the impulse to make unstated contributions.

This ongoing research focuses on what happens when artist statements are both exhibited and performed—when they are deliberately foregrounded. My current focus involves an examination of two exhibitions held six months apart, one in the United States and one in Canada, that moved artist statements from the periphery to the centre of the exhibition space.

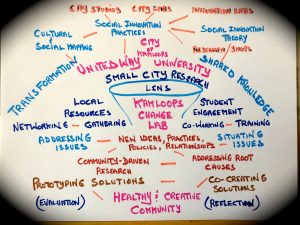

Supported by a research MOU with the United Way, our team has been working on the development of a social innovation “Change Lab.” Our recent C2Uexpo presentation introduced many of our key ideas: “Community Collaboration: A Catalyst for Social Innovation.” Panel presentation (with Danalee Baker, Ann McCarthy, Sukh Heer Matonovich, and Troy Fuller), Simon Fraser University.

Supported by a research MOU with the United Way, our team has been working on the development of a social innovation “Change Lab.” Our recent C2Uexpo presentation introduced many of our key ideas: “Community Collaboration: A Catalyst for Social Innovation.” Panel presentation (with Danalee Baker, Ann McCarthy, Sukh Heer Matonovich, and Troy Fuller), Simon Fraser University.

It is our contention that the small city—and by extension the development of effective growth coalitions and social innovation initiatives with small cities—requires attention to the distinctive experiences, voices, and relations associated with smaller, less central places. In Kamloops, we are developing a Change Lab, employing the lens afforded to us by the growing body of small cities research as a means of adapting and inventing appropriate practices, processes, and approaches. We approach with caution the conventional “Creative City” script; and we remain open to the proposition that the discourse of technological innovation may work against cultural and social regeneration in smaller places. Ways of getting things done differ depending on community scale, network formality, and the sense of familiarity linked to shared proximity and repeated exposure. We speculate, for example, that direct contact with and involvement of community change makers differs depending upon the size of the city—a matter of “privileged access” in large metropolitan centres vs. “distributed access” in smaller communities. In brief, then, as we develop the Kamloops Change Lab we look forward to documenting and exploring further how context, in particular community scale, impacts social innovation theory and practice.

“Faces of Undergraduate Research: Underrepresented Students and TRU’s The Knowledge Makers” (an ongoing interest)

“Faces of Undergraduate Research: Underrepresented Students and TRU’s The Knowledge Makers” (an ongoing interest)

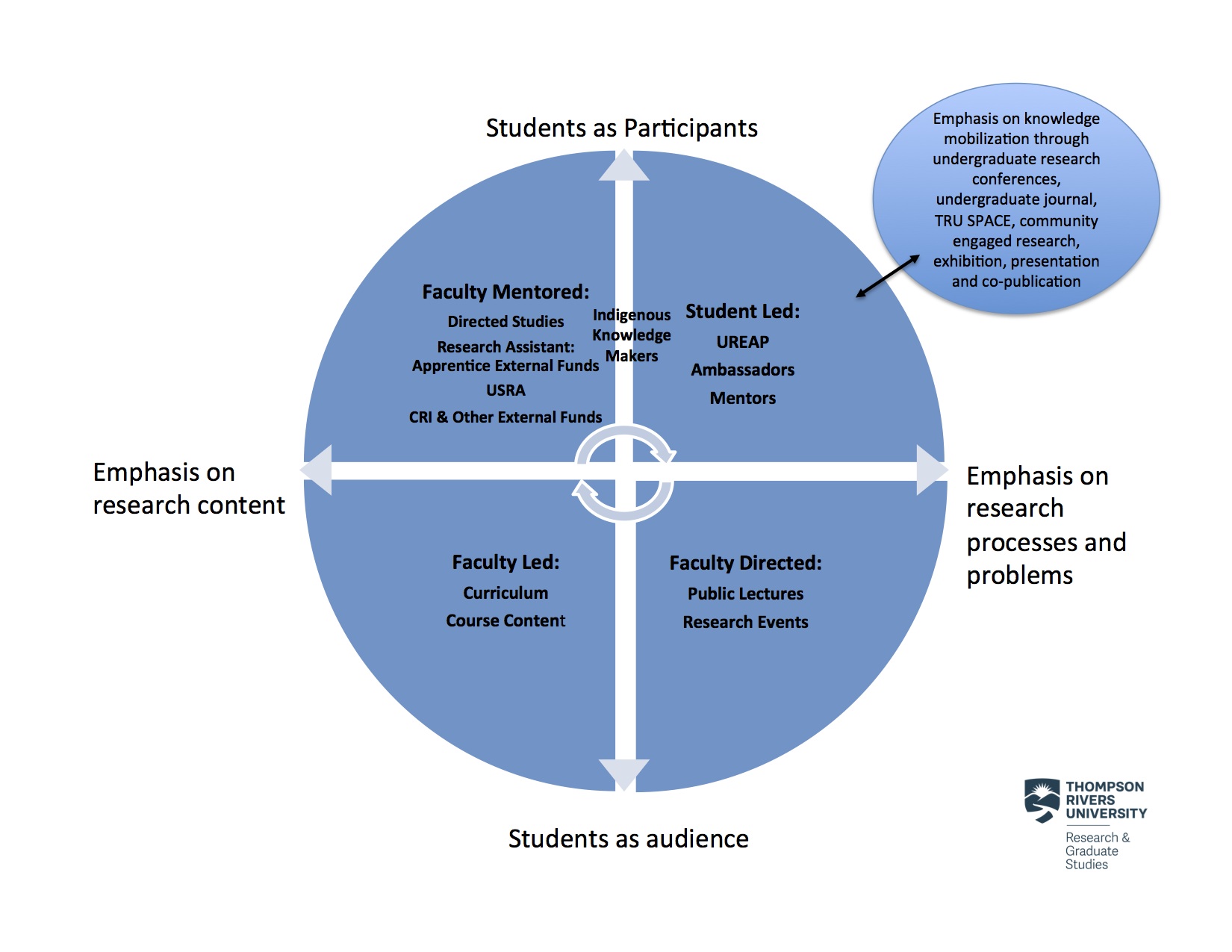

My understanding of undergraduate research–especially its pedagogical impacts–has benefited greatly from my work with Dr. Jenny Shanahan (Bridgewater State University). Together we are working on development of a research network and a symposium to address questions of inclusion and exclusion. We know that students of diverse nationalities, fields of study, racial and ethnic groups, gender identities, and socio-economic classes benefit from participating in undergraduate research (UR). Students involved in UR demonstrate higher rates of persistence and degree-completion, campus engagement, academic achievement, self-efficacy, and analytical and communication skills. These benefits derive especially from supportive relationships with faculty mentors and the advantageous opportunities afforded by participation in UR, such as conference presentations. Yet research indicates that access to UR still disproportionately favours economically advantaged students with family legacies of higher education and students in their final year of study who have proven themselves with high GPAs (Carpi, Ronan, Falconer & Lents, 2016; Finley & McNair, 2013; Osborn & Karukstis, 2009). Although early participation in UR boosts first-to-second-year retention and efficient progress toward graduation, most institutions of higher education wait to involve only the most advanced students in faculty-mentored research—those most likely to graduate anyway. And despite evidence that the benefits of UR are most pronounced for students who are underrepresented in higher education, such as first-generation, low-income, and minority-group students, such students are least likely to be awarded UR opportunities (Brownell & Swaner, 2010; Gregerman, 2009; Hernandez, Schultz, Estrada, Woodcock & Chance, 2013; Jones, Barlow, & Villarejo, 2010; Kinzie, Gonyea, Shoup, & Kuh, 2008; Kuh, 2008; Kuh & O’Donnell, 2013; Linn, Palmer, Baranger, Gerard & Stone, 2015; Locks & Gregerman, 2008; Osborn & Karukstis, 2009).

One significant outcome of our work on undergraduate research is the co-development of the Canadian Undergraduate Research Network (CURN), a website created by students for students:

My point of entry into a conversation on underrepresented student researchers begins with TRU’s program for Indigenous researchers, the Knowledge Makers. I want to note at the outset that my interest in this program does not yet constitute a fully realized research study; but for the last two years I have been invited to meet with the students during their workshop sessions, and to speak at their annual research dinner. In addition, I’ve been asked to contribute two short pieces of writing to the Knowledge Makers Journal. As a result, I’ve been giving considerable thought to the notion of “making knowledge” and its relationship to the creation of UR opportunities. What strikes me initially is that the opportunity for learning, especially when we seek to include all students, becomes highly reciprocal.

Eber Hampton (1995) published an article slightly over two decades ago in the Canadian Journal of Native Education titled “Memory Comes Before Knowledge.” An extraordinarily profound and provocative title: It points to the multiple ways our individual and collective pasts inform the present; but more important still, it underscores a universal truth: that contributions to new knowledge are built upon, shaped by, and filtered through past experiences and understandings.

I want to reflect on the name of TRU’s educational program, the Knowledge Makers, for I think it too embodies the premise that memory comes before knowledge. I’m drawn to the proposition that knowledge is something “made.” We speak more often of discoveries and innovations—as if new knowledge has been hiding or is an extant discovery simply needing a clever twist or refinement, or a novel technical adaptation. To speak of making knowledge, however, is to invoke consideration of process, of qualities, of potentials and of materials. The celebrated Canadian poet Earle Birney preferred using the word “makings” rather than “poems” when describing his writing: partially because makings sounded for Birney less pretentious, but also because it spoke to the craft of writing, in particular to the shaping of words and ideas over a period of time.

In “El Greco Espolio” he subtly equates writing with carpentry, noting the fierce concentration and physical skill required for both: “The carpenter is intent on the pressure of his hand on the awl and the trick of pinpointing his strength through the awl to the wood which is tough”

Haida artist Bill Reid similarly reminds us of how we employ memory intentionally as a prerequisite to knowledge making: “I wish that the objects which come from my hands play the role of “revelators” of ancient representations. It is my hope that the people of today and of tomorrow become aware of the existence of the Northwest Coast and feel enriched by the knowledge they will acquire from this extraordinary testimony….”

Knowledge is not simply discovered: it is made through physical and mental effort; informed by past practice and history; negotiated through tradition, relationships, and received ways of thinking; and deepened through personal and community engagement. To be a “knowledge maker” is to embody and honour memory as the prerequisite for contributing new understandings, new ways of knowing.